There are thousands of articles written about diversity and inclusion in the workplace, and everyone talks about gender and age discrimination. But in the D&I room, there’s a bigger, uglier elephant that no one likes to address: name bias.

At Harver, one of our core values is Landing on the right side of history. In practice, this commitment to do the right thing acts as a guiding principle for everything we do, from business strategy to product development, and it shapes our mission statement, which is making hiring fair for everyone.

This means that aside from our commercial goals, we go the extra mile to ensure that all candidates processed through the Harver platform are given an equal chance to land a job.

The problem, though, is that no matter how accurate and unbiased a pre-employment assessment is, most companies still filter candidates manually and rely on recruiters to decide who progresses to the next stage. In hourly jobs, this is exactly where name bias hits the hardest.

To understand better why this happens and how big the issue is, I looked at name bias in the volume hiring space, across industries and geographies.

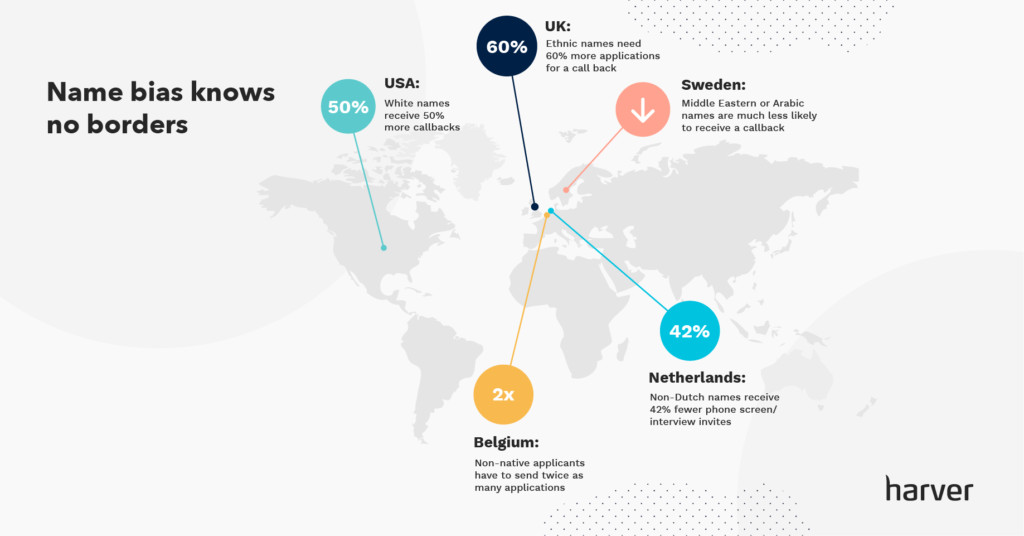

Name bias knows no borders

If you ask a recruiter whether they discriminate against certain candidates, they’ll inevitably say “no”. However, name bias seems to influence virtually every hiring process on the planet, and candidates with ethnic-sounding names are more likely to be negatively impacted by this form of unconscious bias.

Non-white candidates have a disadvantage in callbacks for interviews compared to their white counterparts with similar qualifications, as shown by a meta-analysis published in 2019.

This happens across countries and affects a wide range of industries and roles.

In the UK, for example, candidates from ethnic minorities have to send 60% more applications in order to receive as many callbacks as native majority candidates, and the discrimination experienced by minority groups is heaviest for applicants from Black African or MENA countries. This happens in both high-skilled occupations, such as marketing or sales roles, and low-complexity jobs, such as store assistant, cook, admin clerk, or receptionist.

In Belgium, research conducted by scientists at the Ghent University found that compared to Belgian-born applicants, candidates with foreign-sounding names are equally as likely to be invited to job interviews when they apply for occupations for which vacancies are difficult to fill, such as accountants or even call center agents. But when it comes to low-complexity roles that require no experience, such as cleaners, warehouse workers, or commercial clerks, for which the labor market tightness is low, non-native applicants have to send twice as many applications.

The same thing happens in Sweden, where field experiments have revealed that applicants with Middle Eastern or Arabic names are much less likely to receive a callback than their native counterparts.

In The Netherlands, employers are less likely to check the resumes of candidates with Arabic names, compared to applicants with Dutch names, in the first phase of the recruitment process.

Dutch applicants are twice as likely to proceed further in the application process when compared to Moroccan candidates, the unequal treatment occurring in all the steps of the recruitment process. From the four largest non-Western groups in the Netherlands, minorities who are Moroccan, Turkish, and Antillean are much more discriminated against by employers.

Name bias is affecting the U.S. labor market too, where studies show that applicants with white-sounding names receive 50% more callbacks for interviews, and increasing resume quality can help candidates with white-sounding names more than they help applicants with black-sounding names.

In the Netherlands, the retail industry is the most tainted

These findings are in line with our research on the Dutch labor market. In our study for Harver, we focused on low-complexity jobs in retail, customer service, logistics, warehousing, and administration, at the top 500 companies in the Netherlands, including governmental organizations.

“The goal of our research was to see if and how much name discrimination occurs in the Dutch labor market.“

— Tessa te Kaat, Sr. People Science Consultant at Harver

We applied to around 1,200 jobs, using Dutch and non-Dutch names, with CVs that were almost identical. The type of work experience, skills, hobbies, education, as well as the place of living, the distance from the job location, all of these were kept similar. The only difference on the CVs was the names.

We found differences between governmental and non-governmental organizations, between regions, and between industries.

For example, in the customer service sector, there was significantly less discrimination than in retail. We believe that this is because there is always a demand for customer service agents. In retail, on the other hand, the discrimination against non-Dutch names was the most prevalent. In the logistics sector, there weren’t significant differences between the responses received by the Dutch and non-Dutch applicants.

The retail industry had the worst discrimination wherein non-Dutch candidates were

3x (328%)

as likely to be rejected compared to Dutch candidates.

Source: Harver

The gray area between the rejections and positive responses was interesting to look at; more than half of the applications didn’t receive any reaction, and this happened across industries.

When we looked at what happened when one application hadn’t been given a positive or negative outcome, we found disparate treatment. When a Dutch candidate had not heard back, 83% of the non-Dutch candidates were already rejected. This was compared to 42% of the Dutch candidates in the reversed scenario.

This is a critical difference in candidate experience, because not hearing back at all could still be a sign that the recruitment team is holding your application for a future opening.

“We can’t know for sure, but the assumption is that for roles where a non-Dutch person wasn’t even considered, the Dutch person was still given a chance.”

Tessa te Kaat

Overall, candidates with a non-Dutch name received 42% fewer phone screen/interview invites than candidates with a Dutch name. The public sector was more biased than the private one: 36% more candidates with a Dutch name were given a positive outcome compared to candidates with a non-Dutch name.

Region Randstad – which includes Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and The Hague – proved to be the most biased region, with the largest difference (50%) in invitation rates. Overall, there was no additional difference between men and women: non-Dutch males and females were invited at almost the same rate.

Name discrimination starts in the pre-selection phase

Although D&I initiatives are high on the agenda of employers, name discrimination is still present in the recruitment process.

Many organizations are saying they take measures to fight discrimination or that their leadership values diversity, and point to their D&I policies to back up these statements. But often the reality is that nobody continues to ensure that these policies are still followed after the initial enthusiasm wears off.

When applicants are rejected after an interview or introductory meeting they often receive feedback that there was a more suitable candidate. Yet, proving discrimination in the pre-selection phase, where candidates are assessed based on their CV and cover letter alone, is extremely difficult.

And the pre-selection phase is where this behavior starts, in most cases, despite the fact that employers are legally obligated to have guidelines and working methods in place to avoid biased hiring practices.

In the Netherlands, for example, you can file a complaint with the Institute for Human Rights if you think you were treated unfairly, but very few people do it, because they think they don’t stand a chance of proving it. Even if they have some sort of proof, it would still be too late, because no one wants to work for a company that has already rejected them.

But why does all of this happen? Where does name bias come from, and why is it still affecting the workforce in 2021?

With bias here to stay, job seekers … adapt

An explanation for the occurrence of name bias in the recruitment process refers to ethnic penalties.

This states that second-generation migrants have poorer outcomes not due to observable demographic or socioeconomic factors, but due to the ethnic or racial attributions that create societal obstacles for their integration in the labor market. Even when raised and educated in the same country in which they apply for jobs, they are at a disadvantage in the labor market.

And this is not new. If we look at the Dutch labor market, for example, there is research work dating back to the ’70s that showed that the likelihood of receiving a positive response from an employer was about 30% lower for applicants with Moroccan, Spanish, or Surinamese names compared to the majority.

Another possible explanation is the social dominance theory, which emphasizes the persistence of discrimination against non-whites. White immigrants are disadvantaged relative to white natives but less so than the ethnic minority groups and this difference between white immigrants and natives is not significant.

What’s certain is that name discrimination still affects the hiring process. And although it may not seem important, because we’re talking about entry-level jobs where the pay is low, the stakes are actually high for these positions.

“We – as Harver – can’t influence how biased a recruiter is, but we can make sure that once they start looking at a candidate, they are less biased because they see a score, not a name.”

Tessa te Kaat

For the people applying to these roles, fair treatment is essential. From a candidate’s perspective, if you can’t get a job in a warehouse or grocery store because of name bias, you cannot get a fair chance at a career.

Some candidates aren’t given as many opportunities to be successful in the labor market in general, because of several factors, such as social status, education level, or lack of a professional network.

Oftentimes, name bias adds yet another hurdle for them.

The result? Job seekers “whiten” their resumes to increase their chances of landing a job. Candidates engage in such behaviors at the earliest stages of the application process, before their minority status would become obvious to employers.

If hired, minority entry-level employees such as grocery store cashiers perform worse when assigned a manager who is more biased against them. They are absent more often, spend less time at work and are slower, taking more time between customers. This manager bias affects the average performance of minority workers, who perform better when assigned managers who are unbiased.

So, what can employers do to fight name bias?

Fighting name bias starts with awareness (and tech)

Combating name bias in recruitment starts with being aware of its occurrence, and effects, and continues with equipping your talent acquisition teams with the right tools for minimizing bias when screening, assessing, and selecting candidates.

“Our responsibility is to expose the problem, inform recruiters, and equip them with the right tools for eliminating bias from the hiring process.“

— Tessa te Kaat, Sr. People Science Consultant at Harver

Human bias is present in each part of the hiring process, and that’s why we, at Harver, are building technology that not only provides fair assessments to all candidates, but also automates the process and uses objective, unbiased criteria to enable data-driven recruitment decisions.

We can’t influence how biased a recruiter or hiring manager is, but we can make sure that once they start looking at a candidate, they’re less biased, because they see a score, not a name. And this score is meant to be an objective assessment of someone’s suitability for the role and company.

Harver provides scientifically validated pre-employment assessments that are designed to make the hiring process fair for all candidates. At the same time, we support our clients with a dedicated D&I Insights dashboard that makes it easy to track and visualize diversity and inclusion metrics, including name bias.

We believe that it’s our responsibility to expose the problem, inform recruiters, and equip them with the right technology and tools for reducing or eliminating name bias from the hiring process.